|

by Richard B. Bliss*

Institute for Creation Research, PO Box 2667, El Cajon,

CA 92021

Voice: (619) 448-0900 FAX: (619) 448-3469

"Vital Articles on Science/Creation" August

1988

Copyright © 1988 All Rights Reserved

All too often the elementary teacher sees science as an almost impossible challenge. To many teachers, science is relatively unimportant—a subject that can be treated superficially without any real damage to the pupil's overall learning. Some teachers say that science is too difficult for them; others claim it requires too much money for schools on a limited budget, and there are other excuses. Nevertheless, teaching science in the very early grades can have many interdisciplinary benefits to that pupil.

We believe a good start toward solving these problems for the home school and Christian school has been made in ICR's new activity-oriented "Good Science" curriculum, developed by the writer, who has attempted to integrate all of the attributes of an excellent science curriculum in a new curriculum called "Good Science—Under the Attributes of God." In this curriculum, home school parents and Christian teachers are shown how to teach science to their children in a simple, inexpensive, and proven way that will also continuously glorify our God of creation. We in Christian education must be willing to extend ourselves to give the best—not just run-of-the-mill-science instruction to our pupils. Christians should be motivated to pursue excellence in science education.

In addition to seeking an exemplary approach to science for the Christian schools, the curricula should also be centered upon the attributes of God. The "Good Science - Under the Attributes of God" plan is not only centered upon God's attributes, but also follows the finest principles of child development. This approach to science education is based upon the tested and proven "process skills of scientific inquiry." In addition, these skills are the teachable components of the so-called scientific method. Incorporated in this curriculum are some of the major concepts of science, which are built into a "scope-and-sequence" plan that will bring new and vital experiences from the real world around us to the pupil. Starting from preschool experiences in the physical and life sciences, through the sixth grade, the pupil learns how to utilize the skills of scientific inquiry—which constitute the essence of science—through the use of important scientific concepts. These concepts include: populations, environments, ecosystems, variables, relativity, energy, models, and many others. Inquiry skills are then developed within this series of important concepts in science.

The aims and objectives of "Good Science" curricula are designed to: a) develop the necessary skills in the critical thought and decision-makin,process, as well as the process skills of scientific inquiry; b) develop activity-oriented materials that are cost effective for all home school and Christian school classrooms; c) develop activities that are challenging at the higher levels of learning taxonomy, as well as being intellectually exciting; d) develop a science curriculum that is interdisciplinary in nature; e) develop a clear creation-centered approach that expresses God as the Creator and Master Designer of all things. Man is always man; dog is always dog; frog is always frog; and plants and animals always reproduce fter their kind.

The "scope-and-sequence" for "Good Science" has integrated some of the finest concepts developed through years of study. "Good Science" has added to these concepts the attributes of the Creator, and has sought to eliminate the humanistic threads in current programs.

In all activities, the Creator is given redit for the order and design that is bserved in the world around us. This scope-and-sequence" illustration for "Good Science—Under the Attributes ot God" provides evidence of God's creation in both the physical and life sciences.

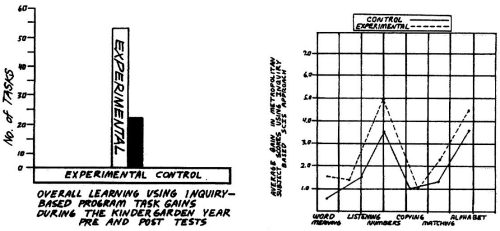

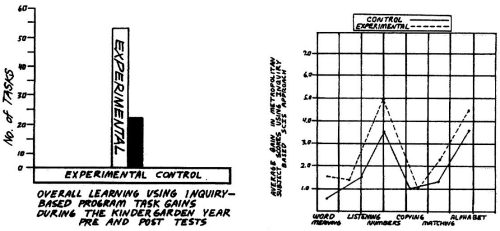

The essential qualities of critical thinking skills are only achieved when pupils are challenged to think creatively; therefore, guided and frequently open-ended inquiry is the rule of the instructional plan in "Good Science." This kind of thinking is generated through skilled questioning by the teacher. Questions such as: "I wonder why?" "Can you tell me more about the guppie?" and "What did we observe today?" are all questions that lead to creative thinking in lower elementary children. It is precisely this kind of thinking that a good science curriculum should establish for the pupil, and therefore a conscientious effort has been made to incorporate it in the "Good Science" K-6 series. The natural development from the verbal responses that inquiry activities elicit is that they will enhance reading readiness. Furthermore, through the inquiry approach, the pupil automatically operates at the higher taxonomic levels of learning. The studies given in the graph below show these important spin-offs from science teaching by this method at the lower grade levels:

|

Activity-oriented science can produce a working understanding of the important concepts expressed in the "scope-and-sequence" of the "Good Science" curriculum that is beyond what the standard memory-type curriculum can produce. Notice the data on a most recent study relating to this very issue: (Kyle, 1988).

In addition to this, the program can be fully implemented at a very reasonable cost to the home school parent as well as the Christian school working on a low budget. Equipment and supplies are readily acquired from the grocery store, the local electronics shop, the nursery, the pet shop, and the family kitchen. Some of the most sophisticated observations are made in aquaria and terraria that cost less than $2.00, and are constructed by the pupil. Principles of physics and chemistry are developed at 2nd-and-3rd-grade levels of understanding through simple hands-on experiments. Through the simplest kinds of activities, the pupil is challenged to make observations and draw inferences; however, he never loses sight of the order and purposeful design of the Master Designer.

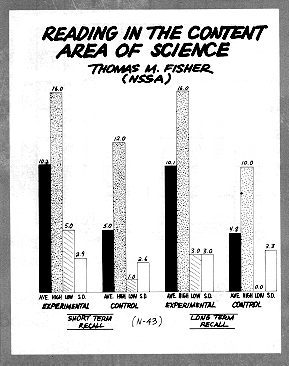

In addition to these exciting and scientifically challenging activities, recent studies have shown that students tested on "Reading in the Content Area of Science" show significant gains in recall—both short term and long term.

This is what we want to see happen in a good inquiry-based program in science. The interdisciplinary effects of this kind of activity-oriented science reaches into the math, reading, and writing programs. The "Good Science" curriculum tries to meet all of the requirements of exemplary science; its most glowing feature, however, is that all of the pupil's inquiry activities are centered upon the Creator and His creation.

Hands-on science alone doesn't always produce the best in science education, but an exemplary science program is not based upon expensive equipment and facilities. The better programs in science are based upon the skills of scientific inquiry and the critical thinking that they develop; but let us not forget that the highest of all thinking must be based upon the Creator who created all things and gave man the mind to investigate His creation.

Bibliography

1. Bliss, Richard B. (in cooperation with Research and Development, Unified School District, Racine, Wisconsin.), Overall Learning Using Inquiry-Based Program (SCIS), Task Gains During Kindergarten Year, 1977.

2. Bloom. Benjamin S. (ed.) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, (New York: Longmans, Green, 1956).

3. Elementary Science Study (ESS) (McGraw-Hill Co., New York, N.Y., 1960).

4. Fisher, Thomas M., "Reading in the Content Area of Science," NSSA Summer Issue, p. 6, 1987.

5. Knapp, M., M. Stearns, M. St. John, and A. Zucker, "Prospects for improving K-12 Science Education from the Federal Level," Phi Delta Kappa, May, 1988.

6. Kyle, W., Ronald Bonnstetter, Thomas Gadsden. "An Implementation Study: An Analysis of Elementary Students and Teachers Attitudes toward Science in Process - Approach Versus Traditional Science Classes," Journal of Research in Science Teaching, Vol. 25, Issue 2, February 1988.

7. Outdoor Biological Instructional Strategies (OBIS), (Delta Education, New Hampshire).

8. Renner, John W., Don G. Stafford, William B. Ragan, Teaching Science in the Elementary School (Harper and Row Publishers, San Francisco, 1973).

9. Science Curriculum Improvement Study (SCIS) (Rand McNally and Co., Chicago, 1970).

10. Sciences: A Process Approach (SAPA) (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Xerox Corp., 1967).

11. Their, Herbert D., Teaching Elementary School Science, (Heath Co., 1970).

* Dr. Bliss is Director of ICR's Curriculum Development Division.